These seem to be the levels of complexity in a piece of art - beginning with simple 2 dimensional shapes to the 3D projections of those shapes into forms, then combining modified forms to create figures and posing them to suggest a particular action. Then by combining multiple figures interactively you suggest a bigger action and the beginnings of story. Other elements in the composition also add to the idea of story.

I don’t mean to suggest that there’s some inflexible hierarchy that goes in this specific order all the time, it’s more flexible than that and really these things combine with each other in various ways at every level along the way. You might begin thinking about composition for instance before you completely work out the poses and interaction of figures. They all develop differently.

I just listed the terms in this particular order because it does seem to represent increasing levels of complexity from the basic elements (shapes) all the way to the overarching idea of a story, which is hinted at partially by the piece.

Each leveling-up along the hierarchy is a move from one state to the next in the creation of a piece of art. The ultimate end goal being an image representing a story, with characters engaging each other in some dramatic way. Well ok not always - could be just a character portrait but even then many of these levels still apply, and the secondary character being engaged with might be the viewer.

Example - if you start with a shape - let’s say you draw a rectangle. Project that from 2 dimensions into 3 - visually extrude it up from the surface of the paper and you end up with a block - a form rather than a shape. So it’s a step up in complexity to the next level (3 dimensions rather than 2), and it creates greater complexity, but never in a random way. It’s always very definite and with the end goal in mind. In other words, it’s an evolution toward the ultimate goal, not just added random complexity.

To illustrate this with an example, let’s say you have a form - not just a rectangular block but a modified one that looks like a ribcage. Add some more modified basic forms to it. Depending on how you do this, you can end up with a meaningless jumble of forms that resembles a junkyard, or you could end up with something that looks a lot like a human body.

But at this stage - the shift from form to figure, you need to do more than just make sure it resembles a human (or animal) body. It needs to be posed to suggest a definite action, which suggests some part of a story. And if this is a Heroic Fantasy painting or a panel in a comic book or some other type of art involving conflict, there’s also interaction, meaning the action of this character is in opposition to the counter-action of whoever it’s engaging with.

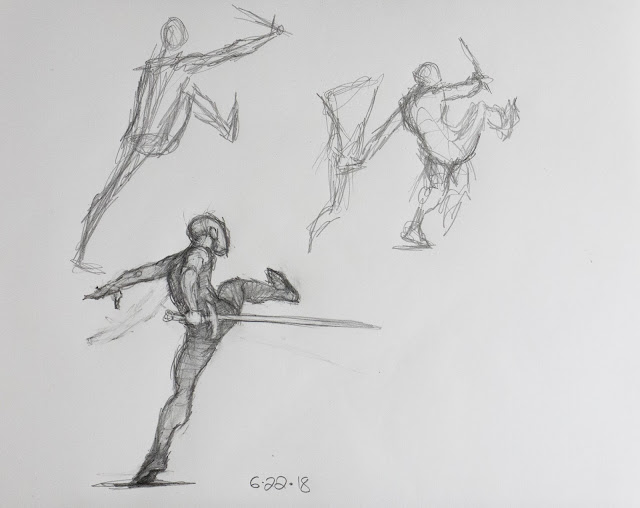

So in the beginning you start with some idea of a story, and you choose a conflict from it (for this example I’m thinking strictly about sword fighting). The way I tend to work is to start from this basic point (at least a vague idea of an overarching story and a more firm idea of the specific conflict I’m depicting). And I try to visualize the pose of my main character, or maybe the secondary one. Or possibly both at the same time, though that can be a lot harder (sometimes it just pops into your head all at once). In the example of my Mouser above, I was reacting to the set of drawings I had already done with him doing a fencing lunge, where he ended up apparently jabbing at his opponent’s knees (need to angle the arm and sword upward to correct that). I wanted to do something less like formal fencing and more dramatic. I also wanted to include some type of grappling or punching or kicking, which makes it a lot more dramatic and personal than just clanging swords together. Street fighting while holding swords is pretty intense stuff!

So I came up with the idea that he would be kicking his opponent in the chest, and at first I thought he should be holding his sword up to block a downswing from the opponent, but that straight arm looked really awkward (as did the straight legs and back-leaning torso). I doodled randomly a bit trying to find a way to get some nice curving gesture in and make it look more graceful, and after a couple of attempts (in which I demonstrate my tendency to scratch around a lot when I don’t understand what I’m drawing clearly) the pose resolved itself. The moment of clarity hit when I suddenly understood the pelvis needs to be in line with his legs - as soon as I sketched that in everything else began to quickly fall into place.

What it means is, the pose needs to represent some kind of coordinated action - not just aimlessness. When his pelvis was at a 90 degree angle to the line of his legs, it worked against the forward action, but when I brought it into alignment, the forward thrust through the legs into the opponent’s (as yet invisible) chest became palpable and powerful, and the pose took on some kind of life.

This is what you’re looking for at each stage - you’re moving to a new level of expression and it should bring a new sense of liveliness or life (need to find better words for it) or drama. It needs to increase the drama, not detract from it.

Keep in mind, the order in which I listed the stages is only the order of complexity of them - not the order you move through. For example, in drawing this figure I began by thinking in loose general terms of a vague pose, and sketched in a sloppy gesture or stick figure suggesting some version of the pose. I had some notion of the action and interaction in mind as well, all very loosely. I made a few changes by drawing new versions, still very loose and gestural, until the idea suddenly solidified and I drew it again - this time it looked much better. As you can see though, I erased the back arm and changed it to suit the pose better (still not quite right). And though I like it, I see it needs a lot of development still. Proportioning is strange; he looks like a little boy with a big head and short skinny arms -- the farther hand is too big and the nearer one too small (should be reversed according to the rules of perspective). And that back heel needs to be down solidly on the ground. I also need to sketch in his opponent and see how they’re interacting with each other - that might suggest some further changes in the Mouser’s pose.

No comments:

Post a Comment